This article is based on nothing more than some internet babble I’ve read over the last few weeks and although it did form part of the basis for my decision to swap my APS-C format Nikon D3300 for a m4/3 format Olympus EM1 Mk2 it’s not particularly scientific and most certainly skips or ignores some aspects of the subject that are probably important!

Briefly there are many types of camera, but they all incorporate a sensor, which is a device that converts light captured by the camera into a digital form that can be stored on media such as a SD card etc. Note: the sensor doesn’t produce the photograph, just the light data in digital form which a processor of some kind can then convert to a photograph.

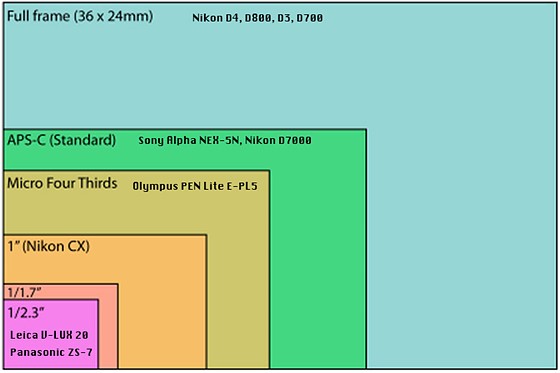

Different cameras have different sized sensors. This image shows common sensor sizes (though not actual size!) :-

As with many things, larger is often better, and professional photographers will most likely use cameras with a “full-frame” sensor. These sensors are so-named because they are the same size as the film once upon a time used in professional SLR cameras.

However bigger is also more expensive, so many consumer DSLR cameras use the APS-C size, often referred to as “crop-sensor” cameras, because they can be related to full-frame cameras using a “crop” factor. For Canon APS-C cameras a crop-factor of 1.6 is used, for all other makes a APS-C camera uses a crop-factor of 1.5. Besides APS-C another common sensor size is “Micro 4/3rds” (m4/3 or MFT for short), a sensor developed and promoted by Olympus and Panasonic. m4/3 cameras have a crop-factor of 2.

What this means is whatever the actual physical properties of a lens may be, you apply the crop-factor when using them on crop-sensor cameras. For example, a lens with a focal length of 100mm will behave as if it has a focal length of 150mm (100 * crop-factor of 1.5) on a APS-C camera (or 160mm if it’s a Canon APS-C camera) and a focal length of 200mm on a m4/3 camera (100 * crop-factor of 2).

Aperture is also multiplied by the crop factor. So an f/4 lens, for example, has an effective aperture of f/5.6 on a 1.5 crop-sensor camera, and f/8 on a m4/3 camera.

Of course the physical properties of a lens never change, they only “behave” differently on cameras with different sensors, and that’s because focal length, for example, is related to angle of view, and it’s the angle of view which changes with sensor size, and aperture is related to depth of field, and it’s depth of field which changes with sensor size. In other words different sensors produce results which are “equivalent” to whatever those results would be if those lenses actually did change their physical properties. And it’s this term “equivalent” which is often used in photography when comparing cameras and lenses.

When I was looking at buying more lenses for my Nikon D3300 I had to take into account the 1.5x crop-factor provided by its APS-C sized sensor. The 70-200mm f2.8 pro lens I was interested in, for example, is equivalent to a 105-300mm lens on the D3300, and as such might not have provided the benefits I was looking for. When photographing Oval track motorsport the 105mm (equivalent) minimum focal length might have been too long, I’d have been better served with the 24-70mm f2.8, which is equivalent to 36-105mm on the D3300.

Of course, this could be (and often is) actually considered a benefit of crop-sensor cameras, you get a certain amount of “free” extra reach. But there are drawbacks as well. A full-frame sensor captures more light, because it’s bigger. It’s simple physics. Bigger sensor = more light captured = more data upon which to base the digital image = better quality image, at least when comparing the same megapixel count. A 20Mp full-frame camera will capture approx. twice as much light as a 20Mp APS-C camera, and approx. 4 times are much light as a 20Mp m4/3 camera, making the image twice, or 4 times, more detailed, or less noisy, or containing a higher dynamic range or indeed all of these combined. That’s why pro’s use full-frame, they generally produce better images.

From the above it might seem that full-frame is “better” all round, and that the only reason you’d not go full-frame is because you couldn’t afford it. But apart from the apparent changes in focal length and / or depth of field alluded to above, which might be a good thing or a bad thing depending on what you’re photographing, there are benefits to be gained from reducing sensor size which should be taken into consideration.

Olympus and Panasonic m4/3 cameras use a mechanism called IBIS (In Body Image Stabilisation) to reduce the effect of camera shake, enabling photos to be taken at (much) lower shutter speeds than might otherwise be the case. They do this by moving the sensor inside the camera body to (try to) compensate for camera movement. Very few APS-C cameras do this (Pentax?), and no full-frame that I know of, because the bigger the sensor the harder it is to move it around effectively.

Top of the range Olympus and Panasonic m4/3 cameras can shoot bursts at insane rates, much faster than even £5,000 top of the range full-frame cameras, because smaller sensor = less data to process = faster processing.

So, like many things in life, which sensor size you go for is a trade-off, does what you gain on the positive side outweigh what you lose on the negative side, and is the financial cost worth it? If you can accept the image quality / noise / dynamic range / depth of field of a smaller sensor, does it really matter how big it is? And if that smaller sensor brings with it smaller, cheaper lenses, better image stabilisation, faster burst rates etc. then why not go that route? These were the things I considered when deciding to swap my APS-C Nikon D3300 for the Olympus EM-1 Mk2 with it’s smaller, but faster, m4/3 sensor.

At the end of the day, if you want to compete with the pros and their £5,000 camera and £10,000 lens, you might find you need to buy that £5,000 camera and £10,000 lens. I decided that was never going to be me, so went the other way, and bought into the Olympus m4/3 system knowing doing so was to make compromises, but that there are many benefits to be had as well.